Remnants of War: Smart Maps Help Teams Locate and Remove Landmines

By Ryan Lanclos.

This story first appeared on the Esri Blog.

Landmines maim and kill long after a conflict ends. Our world is filled with an estimated 110 million of these explosive devices concealed on or just below the ground. Some are the detritus of old wars and conflicts. They are still being used mainly by armed groups in conflicts around the world to obstruct mobility and protect borders. Others were planted more recently, as border demarcations, buffer zones, or tools of psychological terrorism and asymmetric warfare.Representatives from more than 100 countries have signed the Mine Ban Treaty over the last decade, calling for the removal of all landmines and disposal of millions of stockpiled devices. To reach this goal, demining teams will need engagement from many governments along with new technology and demining tools and experts trained in their use.Critically, the teams will also need to determine the exact location of every mine. In demining, a discrepancy of even an inch can be deadly.

The Struggle to Map Minefields

The placement of minefields by national militaries over the last century, mostly for border protection, is often documented and formulaic. But non-state actors such as warlords, insurgents, and guerilla fighters, seeking to sow chaos or evoke fear, place land mines at random—these areas present the biggest challenge to identify and to define the perimeter of dangerous areas.“Most of the minefields we’re dealing with, like in Angola, Cambodia, Iraq or Bosnia and Herzegovina, are literally unstructured,” said Mohammad Qasim Hashimi, global information management adviser for Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA). “Mines could be anywhere. There’s no pattern as such and it is harder to identify exact scope of the problem.”

Demining is one of NPA’s major activities internationally. In partnership with national mine action authorities and other organizations, NPA currently oversees nearly 2,000 people working in 24 countries. Since 1992, NPA has worked in a total of 49 countries and has been instrumental in helping countries fulfill their treaty obligations to remove the threat of landmines. During this span, NPA together with other mine action organizations have cleared all known minefields in 10 countries, most recently Mozambique.

Demining Toolbox and Technology

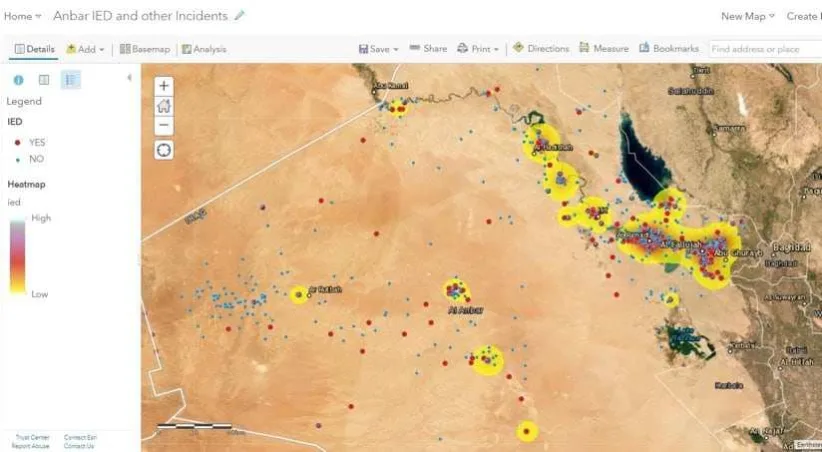

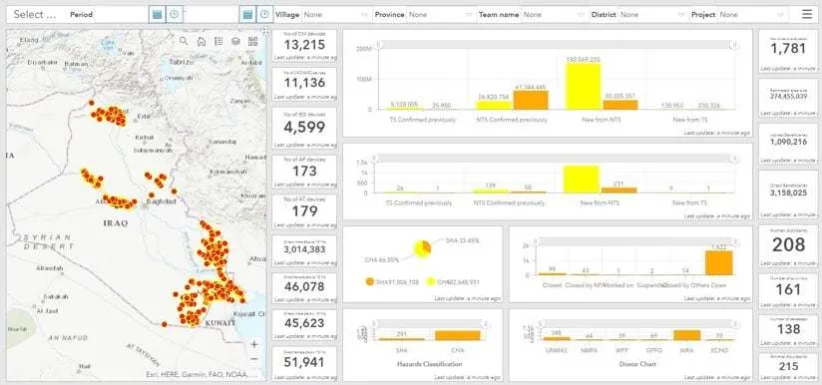

To clear an area of landmines, NPA relies on several tools and techniques. In recent years, deminers have conscripted specially trained dogs that detect mines by scent. In areas where it’s too hot for dogs to work, or around inaccessible terrain, aerial drones provide reconnaissance.NPA staff approach demining from what Hashimi calls an “evidence-based” perspective. Relying on sources as varied as local interviews and topographical analysis, deminers begin by constructing models of possibly contaminated areas. NPA documents the process via a geographic information system (GIS), software that organizes location-specific datasets and displays them on a smart map.

Hashimi has been using GIS for demining purposes for two decades, expanding its use as capabilities advance. Trained in computer science, a profession that uses GIS extensively, Hashimi employs a methodical approach to his job.“Mine action is about collecting relevant data from communities, processing data and making the right decision for your next move in the process,” he said.

Getting the Story Straight

Before NPA demining teams can remove mines, they use GIS maps to pull together all the collected data including historical and any accident points—from interviewing local people, data gathered on site, and other research.“Basically, GIS, helps us make the right decisions, based on evidence,” Hashimi said. “And to have that evidence, we need to know where we’re going to start.”

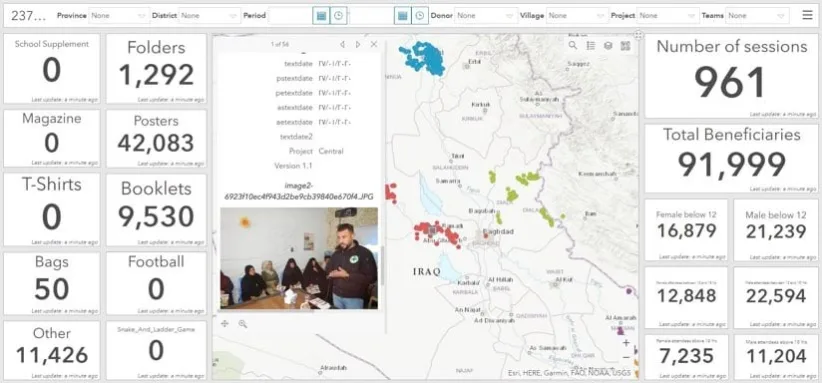

Determining the starting point involves collecting, verifying, and visualizing physical location data. Demining experts begin by considering a small parcel of land. As information accumulates, the contamination model grows larger and more complex. The final action is removal of mines.“We’re using GIS to demonstrate areas based on activities and results,” Hashimi said, referring to areas that have been processed and eventually will be declared mine-free.Fieldworkers use GIS apps to upload information from mobile devices into a central cloud-based database.“GIS mobile apps have really transformed the way we collect data, and also the speed and sophistication of the efforts we do afterwards,” Hashimi said. “We don’t have to carry paper and pens anymore. In the past, there were problems of delay in data transmission from field to the base. You couldn’t make instant decisions, because you couldn’t see what was coming. Second, we had to have personnel ready as soon as the pile of questionnaires came in to start punching in the data to a database system. And the third challenge was suboptimal data quality, because when you start transferring data from paper to digital, there are always the possibility of errors.

By syncing field data and running all input through GIS maps, the process guarantees uniformity and accuracy. In the past, if people were orienting themselves via different coordinate systems, the point of an exact location could vary and that can be disastrous.

Seeing Minefields in Perfect Detail

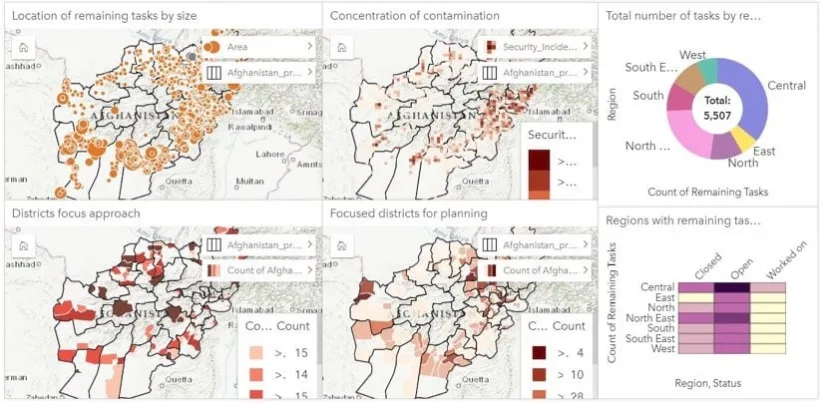

For NPA, technology is fostering a better “big-picture” approach to demining. Analysts can overlay different datasets pertaining to the same location—a move that helps NPA staff with planning and prioritization.

“Let’s say 10 irrigation systems need to be built in a province,” Hashimi said. “You can overlay your information over the land mine contaminated polygons and see which information layer is overlapping. That minefield polygon that overlaps with the irrigation system becomes by default a priority area to be cleared first, and allows local or national authorities to plan ahead and see what needs to be cleared. Often national mine action authorities have sophisticated prioritization criteria with scoring that’s relevant to the country context.”

Working in concert with local governments, NPA teams share maps and location-based analyses to address areas that may contain mines and other explosive ordnance.

“We have specific methodologies to define the scope of the problem,” Hashimi said. “And we have the tools and demining assets to deploy according to the context. Demining is very GIS-based, from the beginning of the activity surveying and marking until the land is cleared and handed back to communities for productive use.”

“As soon as you put data onto the map, it’s not data anymore,” he added. “It becomes information. GIS gives the data its meaning.”

Learn how Esri helps users apply location intelligence to prioritize relief missions.

A Shared Map Prioritizes Demining Efforts

Demining efforts require maps—the more detailed, the better (and safer). But what if the minefield includes the roadsides and sidewalks within a neighborhood and the interior of people’s homes? That’s the case with most of the recent conflicts in places like Syria, Libya, and Yemen, which have transpired primarily in urban areas.

Mines placed in an urban setting pose two main challenges for deminers. People understandably want to return to homes and businesses, placing a greater time pressure on deminers to clear areas quickly. The urban environment is also much more complex. Together, these factors have resulted in an uptick in land mine victims since 2013.

“These areas present a whole new set of challenges for mine action, because the contamination is no longer just on the surface,” said Olivier Cottray, head of information management for the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD). “The contamination is now in 3D.”

Demining experts are exploring the 3D mapping capabilities of geographic information systems (GIS) to address this complexity and to help them in their race against time. 3D models can provide effective information management frameworks against which to map risk and monitor clearance progress. An app-based approach is also helping improve awareness and efficiency of deminers, and thus the safety and speed of demining.

Developers at GICHD have built a suite of tools and apps to address complex demining workflows. This includes an app that engages everyone involved in the decontamination—including residents—to rank hazardous areas on the map. This consensus-building tool helps locals share and spread awareness about areas to prioritize for clearance. This local knowledge sharing helps increase the impact of the demining activity while deminers methodically make their way through an urban setting.“

The web apps have been a game changer,” Cottray said. “They literally put GIS into the hands of decision-makers.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ryan Lanclos is the Director of Public Safety Solutions at Esri where he is responsible for strategic initiatives across public safety and national security. He serves as Esri’s subject matter expert on GIS for emergency management and humanitarian response, and he leads Esri’s Disaster Response Program (DRP) that provides 24x7 GIS support to organizations during disasters. Previously Ryan served as Missouri’s first state geographic information officer (GIO) and GIS advisor for the Governor’s Homeland Security Advisory Council, and participated as an innovation team and expert group member for the United Nations on various initiatives. He most recently served as the director of state and local government at the nonprofit National Alliance for Public Safety GIS (NAPSG) Foundation.